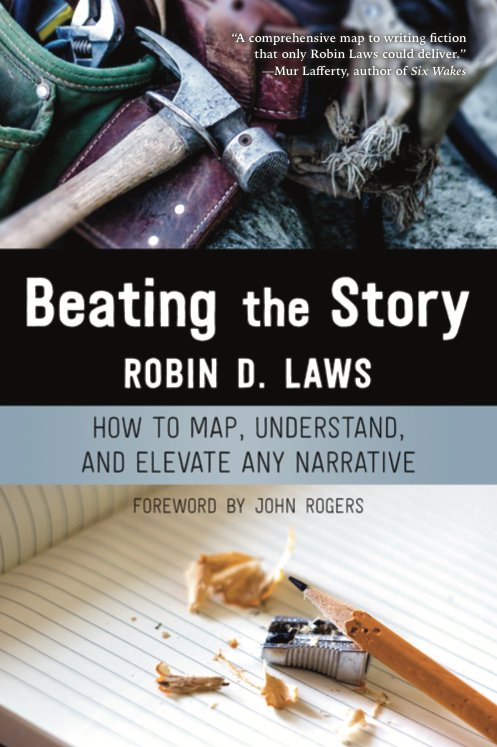

My new book Beating the Story: How to Map, Understand and Elevate Any Narrative examines the building blocks of storytelling, with a particular emphasis on emotional rhythm. Masterful narratives hold our attention by regularly but unpredictably oscillating our response to events between up notes, in which we are moved toward hope, and down notes, in which we fear a disastrous or negative outcome. The beat analysis system, first seen in Hamlet’s Hit Points and expanded in Beating the Story to address the needs of fiction writers in general, allows you to break down and enhance the moment-by-moment flow of any piece. As your needs dictate, this can assist you when you outline or rewrite your own work, or when you comment on or analyze someone else’s story.

The sample narratives mapped in the book, including classic episodes of “Mad Men” and “The X-Files,” come from the world of fiction.

However, non-fictional storytelling works the same way. Everything from TV news reports to books of history, memoir, and journalism likewise hold our attention with a varying emotional rhythm. Documentary films and television do the same.

No more gripping manipulation of emotional rhythm can be found in the non-fiction realm than in the various BBC nature documentaries featuring the compelling vocal quaver of revered naturalist Sir David Attenborough.

An particularly acute example occurs as the final set piece in episode I of “Planet Earth II.” You can find the show on Netflix in many territories. If you’d like to follow along, this sequence starts at the 41:40 mark.

With the help of the free Beating the Story beat mapping tool, let’s break down the sequence.

All but one of the beats we’re about to look at are procedural, in which our viewpoint characters tackle practical, external obstacles. The penguins we are encouraged to identify with face such practical challenges as hunger, crashing waves, and predators.

1) The sequence begins with an intro shot of Zavovdovski Island. The shot’s framing, coupled with the score, emphasize how majestic and impressive this remote location is. Though the sequence hasn’t yet posed a question to orient us in hope or fear, the glorious 4k scenic grandeur nonetheless registers as an up note.

2) But then Attenborough informs us that it’s surrounded by the stormiest of seas and is an active volcano. We’ve seen enough of this nature series already to know that whatever lives here is going to face a struggle for survival. We don’t know what creature we’re worried about, but we have cause to worry. That gives us a down note.

3) With an upturn in the Attenboroughian voice, we see that we’re following the exploits of chinstrap penguins. Who doesn’t love adorable, physically expressive penguins? An up note.

4) We’re told that they have plenty of food. An up note.

5) But to exploit it penguins have to risk their lives. A down note.

6) We watch the plucky penguins get knocked around by the high waves that lash their island’s rocky shore. A second down note.

7) But they seem kind of adept and skillful as they dive off the rocks, although the narration tells us that “life here is dangerous and extreme.” This ambiguous beat plays both ways, with both up and down elements.

8) Cut to: a bucolic shot of the colony. There are benefits, we learn, to living on a volcano. An up note.

9) The lava’s warmth melts snow, we are told. That sounds encouraging—an up note.

10) The warmth brings life. The island is covered in chicks. An up note.

11) We witness a scene of parental care, a moment sure to tweak our sympathy and anthropomorphizing impulses. This up note intensifies our identification with the penguins.

12) But the two chicks we’re focusing on are hungry and waiting for father to return with next meal. This introduces the prospect of fear—what if he doesn’t come back? A down note. The implicit question in any Planet Earth scene is “will this animal we’re being shown survive?” This beat sharpens the sequence’s central question to the more specific “will the father return to feed the chicks?”

13) Cut to the sea: some of the fathers are being eaten by predatory birds called skewers! Bloody penguin flesh in gull-like beaks can only mean a down note.

14) The skewers also harass the colony, flying over it in search of vulnerable chicks. Another down note. The earlier sequence of three consecutive up beats has now been canceled out by as many down beats.

15) As if our avuncular naturalist senses the fear he’s instilled in us, and knows we need an up beat, Attenborough assures us that everything will be fine—

16) —if father comes back soon. Hey, the narrator got our hopes up only to wrench them down again!

17) A shot of the empty sea, accompanied by sad music, delivers another down note.

18) The father penguin surges through water in heroic slow motion, coming to the chicks. An up note.

19) In this narration, the conjunction “but” often signals a turn toward fear. But, we are told, the worst of the journey is still to come.

20) In another fearful moment, a mass of struggling penguins tries to get back up rocks as crashing waves pull them back down.

21) The poor penguins clamber over each other. Another down note.

22) But our hero penguin, the one we’ve been primed to particularly care about, uses his tiny claws to overcome. An up note.

23) He’s up and hopping onto the land. Another up note.

24) But we see another penguin dad covered in blood, and feel his pain. A down note.

25) Our hero has 3 km to go and is loaded down with food. As we see the enormity of his task, we fear for him—another down note.

26) Oh no, we see, this, the largest penguin colony, is dauntingly huge in scope. A down note.

27) But he does this every other day, we are told. Here the “but” again signals a reversal in emotion, but this time reversed, from a previous down note to this up beat.

28) He has trouble finding his nest. A down note.

29) The mother waits, her chicks desperate. A down note.

30) The father recognizes the mother’s cry—salvation is at hand, and we get an up note.

31) He scares off a skewer, for a particularly triumphant up note. (Belay that cynicism. This can’t possibly be a shot of some other random penguin we don’t care about putting the boots to that skewer. Nature documentaries would never play games with us like that. We can totally tell our chinstrap penguin from all the countless others.)

32) At last, mother and father greet each other, for the up note that accompanies any reunion of the central couple.

33) He feeds the chicks. The question “will the father penguin feed his chicks” is answered in the affirmative, for a resounding up note.

34) The couple exchanges a head bob of acknowledgment. Here, in a nature documentary, we get a dramatic beat, in which one character (the petitioner) seeks an emotional response from another (the granter.) The father receives this affirmation from the mother, making this emotional exchange an up note.

35) Now it’s mother’s turn to go get food, so off she goes. We worry for her but are encouraged by Attenborough’s delivery to accept this as a necessary fact of chinstrap penguin existence. You might score it as an up beat, but I’m gonna call it a crossed beat, because I just saw what Dad had to go through.

36) These majestic penguins have it all, the voice-over indicates, as the piece begins its wrap up.

37) This segues into a general paean to islands, concluding the episode on a final up note.

In a ten minute span, that’s thirty-seven beats of intense anthropomorphic emotion, as finely calibrated as any suspense sequence in Hitchcock’s oeuvre.

Narratives, with the ups and downs that keep us riveted, are all around us.

Learn to decode this basic dynamic with Beating the Story: How to Map, Understand and Elevate Any Narrative, from Gameplaywright.

Available at Amazon, Amazon Canada, Amazon UK, and in all digital formats at DriveThru RPG,. Or ask your friendly hobby games store to order it through Atlas Games.