I couldn’t be more pleased that the second anthology of Birds strips, There Goes My Dream Job, includes a foreword by seminal game designer, and my frequent collaborator over the years, Jonathan Tweet. Jonathan, who these days makes Google+ his social media HQ, wanted to post it to the world at large. So here it is.

I couldn’t be more pleased that the second anthology of Birds strips, There Goes My Dream Job, includes a foreword by seminal game designer, and my frequent collaborator over the years, Jonathan Tweet. Jonathan, who these days makes Google+ his social media HQ, wanted to post it to the world at large. So here it is.

If you’re reading this book, you’re one of the lucky people who have discovered Robin D. Laws. In The Birds, he distills his insights into the human predicament down to a hilarious comic strip. It’s all about sex, death, family, lies, and popular culture—doled out in carefully measured doses. It’s rewarding to be one of Robin’s fans, whether you’re playing his games, following him online, or reading his comics. He’s a game designer by trade, but his curiosity and expertise slosh out in all directions. Robin usually has something right (and possibly funny) to say about politics, culture, media, or literature. You can count yourself lucky for knowing Robin’s work, but I’m even luckier. I’ve been a fan of Robin’s work for over twenty years, and he’s contributed to several of my own game designs. My collection of roleplaying games includes many of his innovative and original works. In one of his early games, the supreme god of evil is a twisted version of everybody’s favorite Disney-owned stuffed bear. Robin never bothers to do things the way somebody else has already done it. In another game, one that only Robin could have written, players extemporaneously invent a story that tests their knowledge of cinema genre conventions. Some of his roleplaying games sit on the very small shelf where I keep only those few RPGs that I actually play for fun. In addition to his games, my collection includes his fiction, the Iron Man and Hulk comics he wrote, and the first collection of his comic strip: The Birds.

The Birds reminds me of another cartoon strip written by someone who isn’t a cartoonist, David Lynch’s The Angriest Dog in the World. In Angriest Dog, each strip had the same art and only the words changed. Given how unsatisfying Angriest Dog is, I consider it not so much a comic strip as a work of time-distributed visual art in the structural form of a comic strip. Like Lynch, Robin gives us repetitive, static scenes, but Robin’s strips have the distinct advantage of being funny. The Birds is not just a comic; it’s actually comic.

While the birds in Robin’s strip are often the same from one panel to the next, each character has two distinct expressions. A cartoonist would probably base the two expressions on emotions, such as “happy” and “sad,” or “happy” and “angry.” But Robin isn’t a cartoonist, he’s a Canadian. The two expressions he gives his birds are “gun” and “no-gun.” In practice, the “no gun” expression actually means something more like “no gun (just yet).” With all this gunplay, plus the lies and the spare staging, Robin’s strip reminds me of Quentin Tarantino’s debut film. Maybe it should be called Reservoir Birds.

Cartoonists take pains to show that their cartoon subjects are in motion. They use dynamic poses, motion lines, and spelled-out sound effects to get across the idea that, for example, a little boy and a stuffed tiger are on a runaway wagon careening down a steep hillside. But Robin is not a cartoonist, and that’s what makes his cartoons so outstanding. The poses of his characters suggest not motion but stasis. In the typical scene, each bird is standing still, probably with hands in pockets, possibly leveling a handgun at the other bird.

The instantaneous switch from the “gun” state to the “no-gun” state might be Robin’s way to avoid drawing motion lines. Based on my estimation of Robin, however, I suspect that it’s actually his homage to quantum physics, in which electrons jump from one state to the other with no intermediate step. Reading the latest installment of The Birds is like opening the box to see whether Schroedinger’s cat is alive or dead. “Who drew on whom this time?” we want to know. Like a radioactive isotope, the “no-gun” state inevitably “decays” to the “gun” state. Presumably, the “no-gun” state has a measurable half-life, telling us how many panels it takes, on average, for the gun to appear.

With all the motion happening either off-stage or between panels, the characters are static. These static images are reused from one strip to the next. At risk of overthinking a humorous enterprise, let me suggest that Robin’s subtle humor goes along so well with these motionless, repetitive images because his comic strip is about people being “stuck.” Figuratively, they’re stuck in bad marriages, stuck in bad affairs, stuck in bad friendships, stuck in a bad families—crazy people stuck in a world with other crazy people. The visuals reinforce this theme: the characters are stuck in place. The repetition of the same bird in the same pose pulling the same gun reminds us that these characters have been stuck where they are since the strip began. Application of this insight to the one’s own life is left as an exercise for the reader.

While Robin displays many varied sources of inspiration, in the last analysis, his strip demonstrates his debt to French existentialism. The moral of his comic strip is that, as Sartre succinctly put it, Hell is other birds.

The Birds: There Goes My Dream Job will be available within mere hours from the Pelgrane Press store, and is winging its deadpan, gun-toting way to wherever you purchased The Birds Volume One.

I couldn’t be more pleased that the second anthology of Birds strips, There Goes My Dream Job, includes a foreword by seminal game designer, and my frequent collaborator over the years, Jonathan Tweet. Jonathan, who these days

I couldn’t be more pleased that the second anthology of Birds strips, There Goes My Dream Job, includes a foreword by seminal game designer, and my frequent collaborator over the years, Jonathan Tweet. Jonathan, who these days  If you’re seeking proof that a few months is an eternity in social media land, check this out.

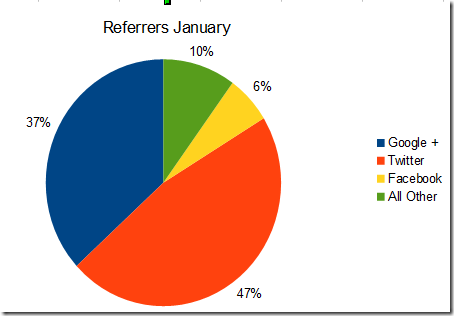

If you’re seeking proof that a few months is an eternity in social media land, check this out.

Progress in moving New Tales of the Yellow Sign from MS to publication continues, with an exciting announcement to come. Lucya Szachnowski has done a bang-up job on the all-important proofreading.

Progress in moving New Tales of the Yellow Sign from MS to publication continues, with an exciting announcement to come. Lucya Szachnowski has done a bang-up job on the all-important proofreading.

During character generation, after

During character generation, after  Welcome again to Scene Study, where we break down dramatic scenes in recent popular entertainment as they might play out in DramaSystem.

Welcome again to Scene Study, where we break down dramatic scenes in recent popular entertainment as they might play out in DramaSystem.

Apropos of his participation in a recent panel discussion,

Apropos of his participation in a recent panel discussion,  Sarah Monette applies her experience of real-life horses to list five ways in which the actual creature differs from its portrayal in fantasy fiction:

Sarah Monette applies her experience of real-life horses to list five ways in which the actual creature differs from its portrayal in fantasy fiction: